how to approach a recipe to cook better part 2

The other day, I pulled an old card out of the recipe box, a Serious Eats jambalaya. Just kidding, I don't have a recipe box.

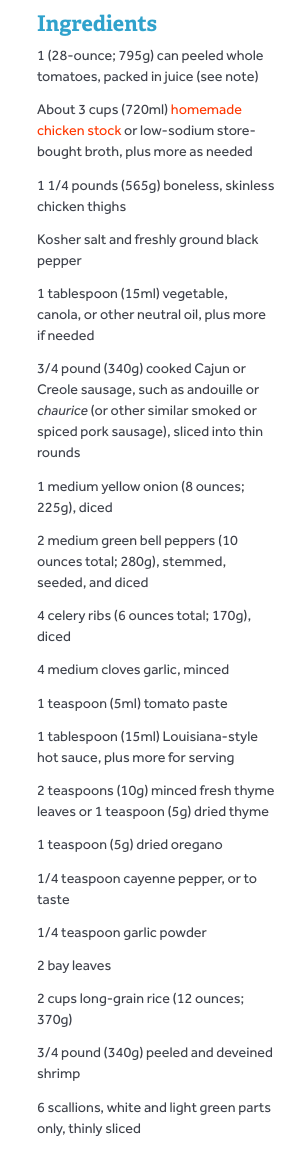

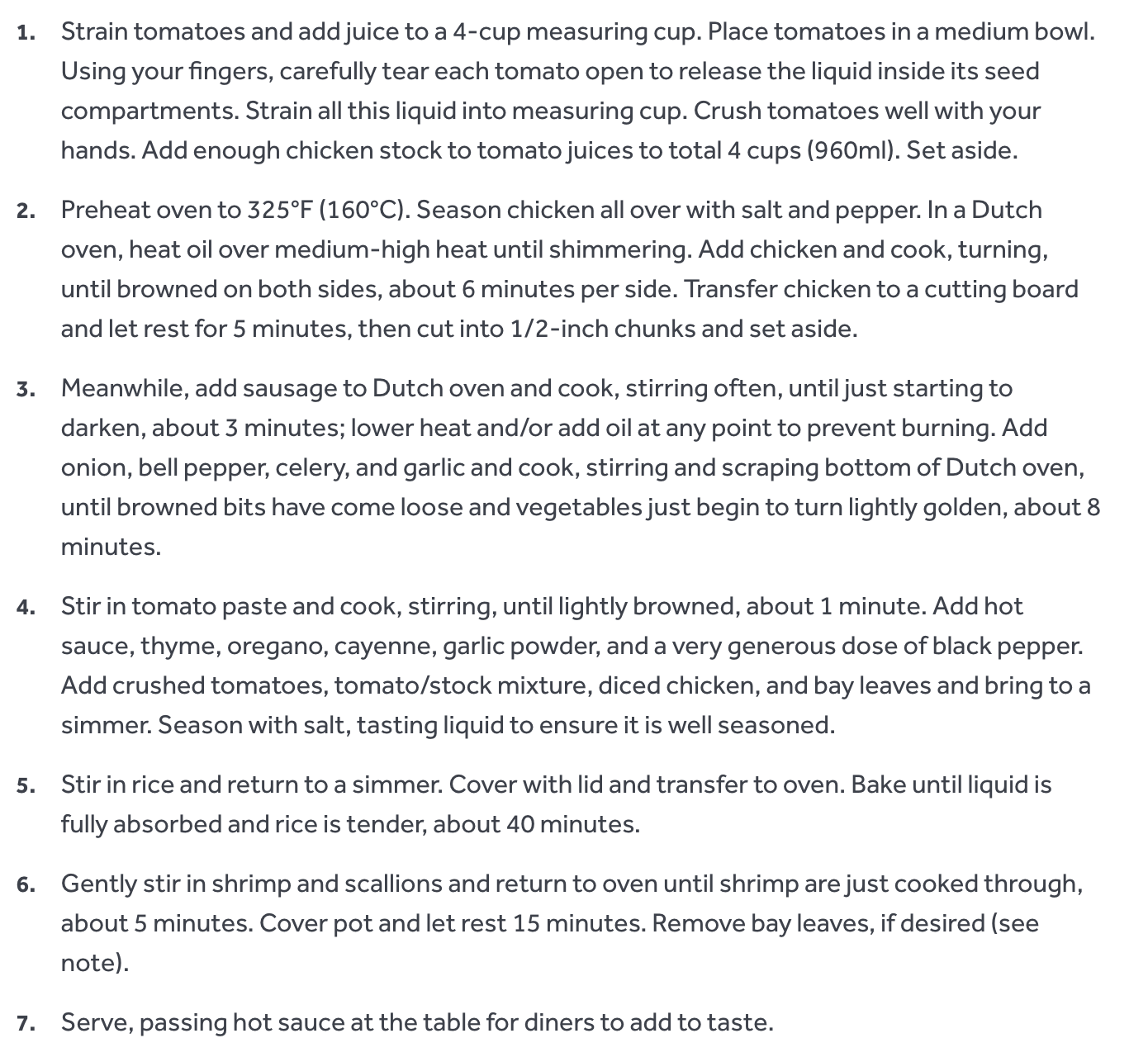

Let's do this recipe breakdown. First thing that happens is I get hit by a wall of text. For many, I feel like this is intimidating enough to say "ah, fuck this," and not do the recipe.

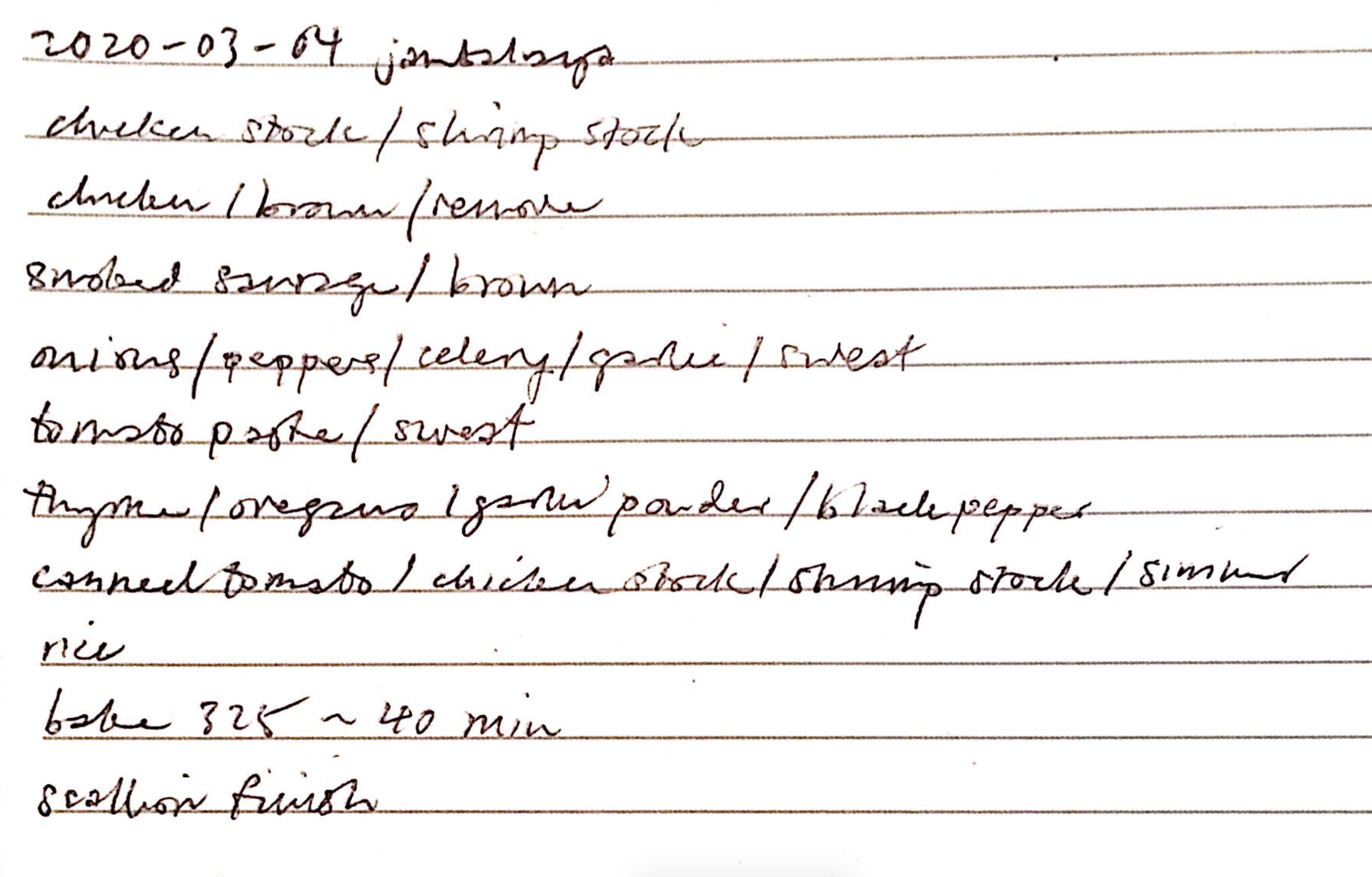

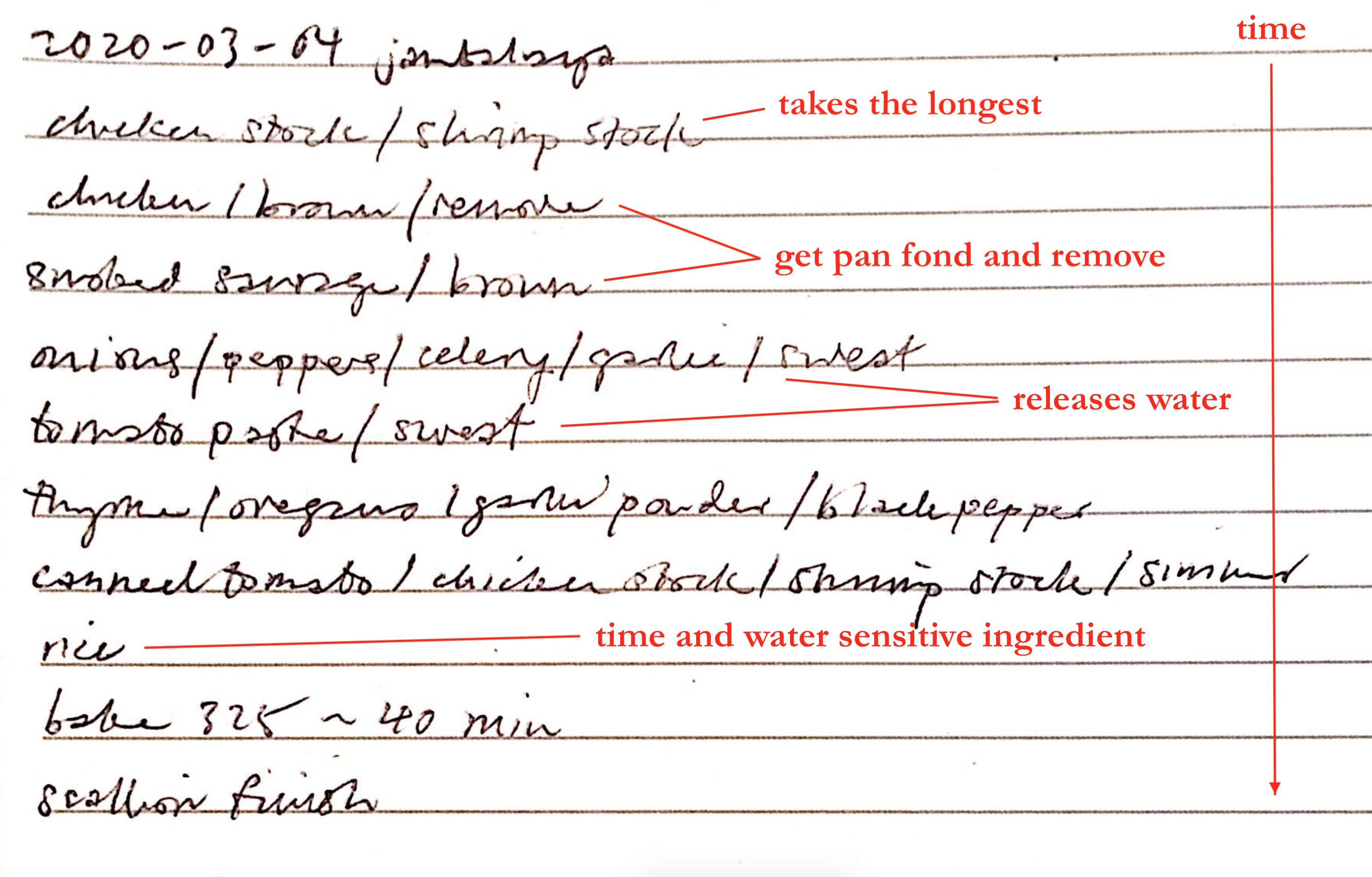

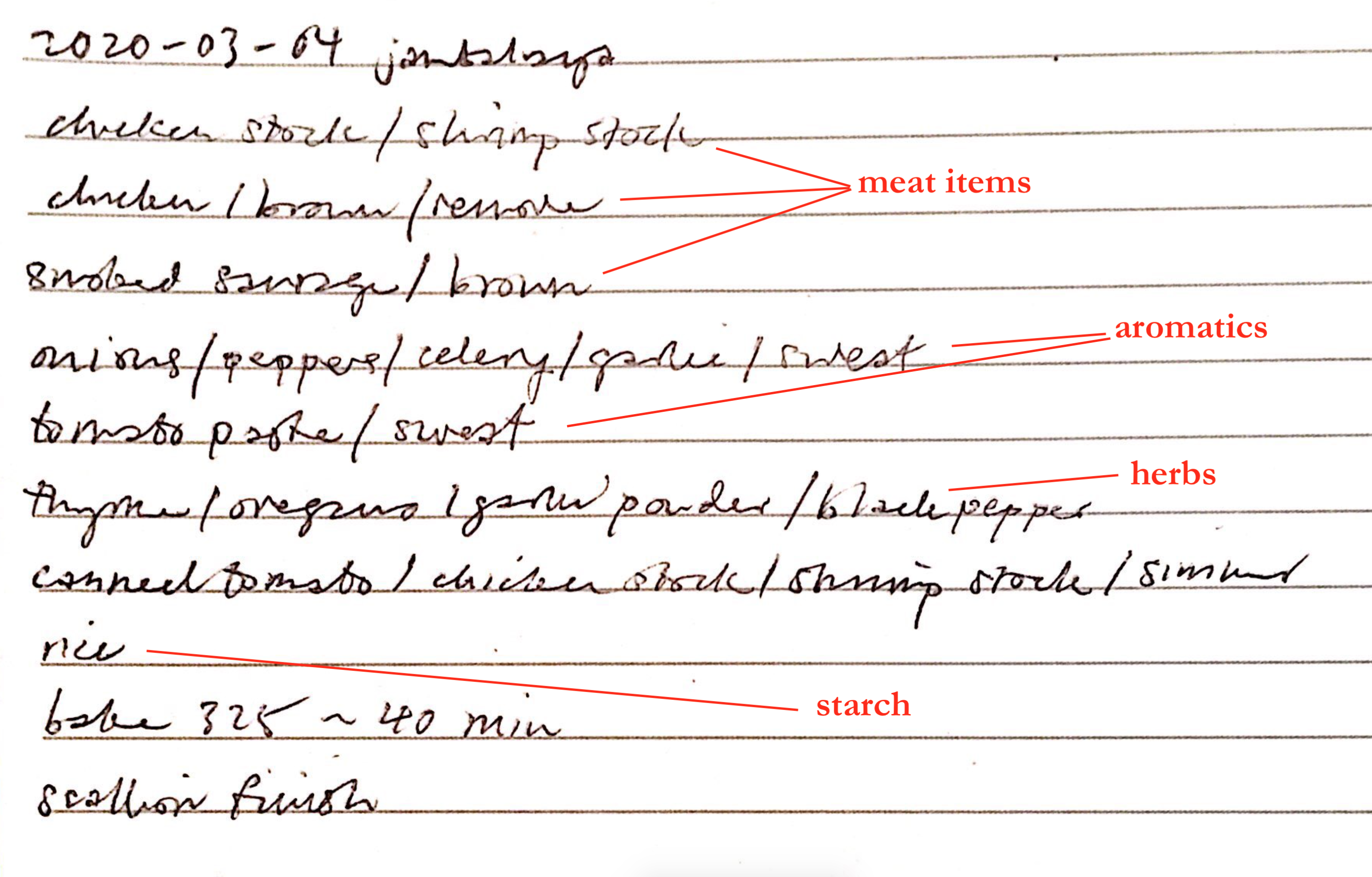

Don't fret. Without getting into quantitative amounts just yet, I immediately short-hand this into a notebook, combining ingredients and the action phrases into a stepwise structure that is done in a more or less chronological manner. I already know the concepts that I'll use, but I'll go over them step by step.

There's three forms of organization that I employ right off the bat with my shorthand.

- timing

- categories

- flavor development

timing

Timing is the first way I organize because this shorthand is eventually what I will reference when cooking.

With regards to timing, the most efficient way to cook is to start with the items that are independent and are used as intermediaries in the recipe, which are also the items that take the longest.

Chicken and shrimp stock are first up, because that takes a minimum of two to three hours. It's also an intermediary. The stock is used in a later portion of the recipe, and I'm pretty sure I don't want to wait an entire three hours to finish the dish. Of course, you can use boxed stock, but…nah.

Come game day, when we execute the recipe, the meat portion also has two timing concepts.

- We sear the meat in order to create the brown bits at the bottom of the pan.

- We remove the meat and add it back later, so we're not completely boiling it to hell while cooking the rest of the ingredients.

If you think about it, cubed chicken, shrimp, and sausage will definitely overcook in a 40 minute oven session after searing. This is why we remove it.

Rice comes last because you want the flavors to have already developed across the liquid before you add a grain that will soak up that flavor.

That leaves the vegetables and aromatics in the middle of the recipe.

Aside from the stock, the rest of the ingredients are dependent steps. The finished dish is dependent on the rice, which is dependent on the vegetables, which is dependent on the flavors of the meat, which is dependent on the broth.

categories

Jambalaya turned out to be an exception, since the chronological nature of the recipe lent itself to a rather neat organization of all the ingredients. This is mainly helpful when you're scouring for ingredients at your local market. It won't be this easy for all the recipes that you cook.

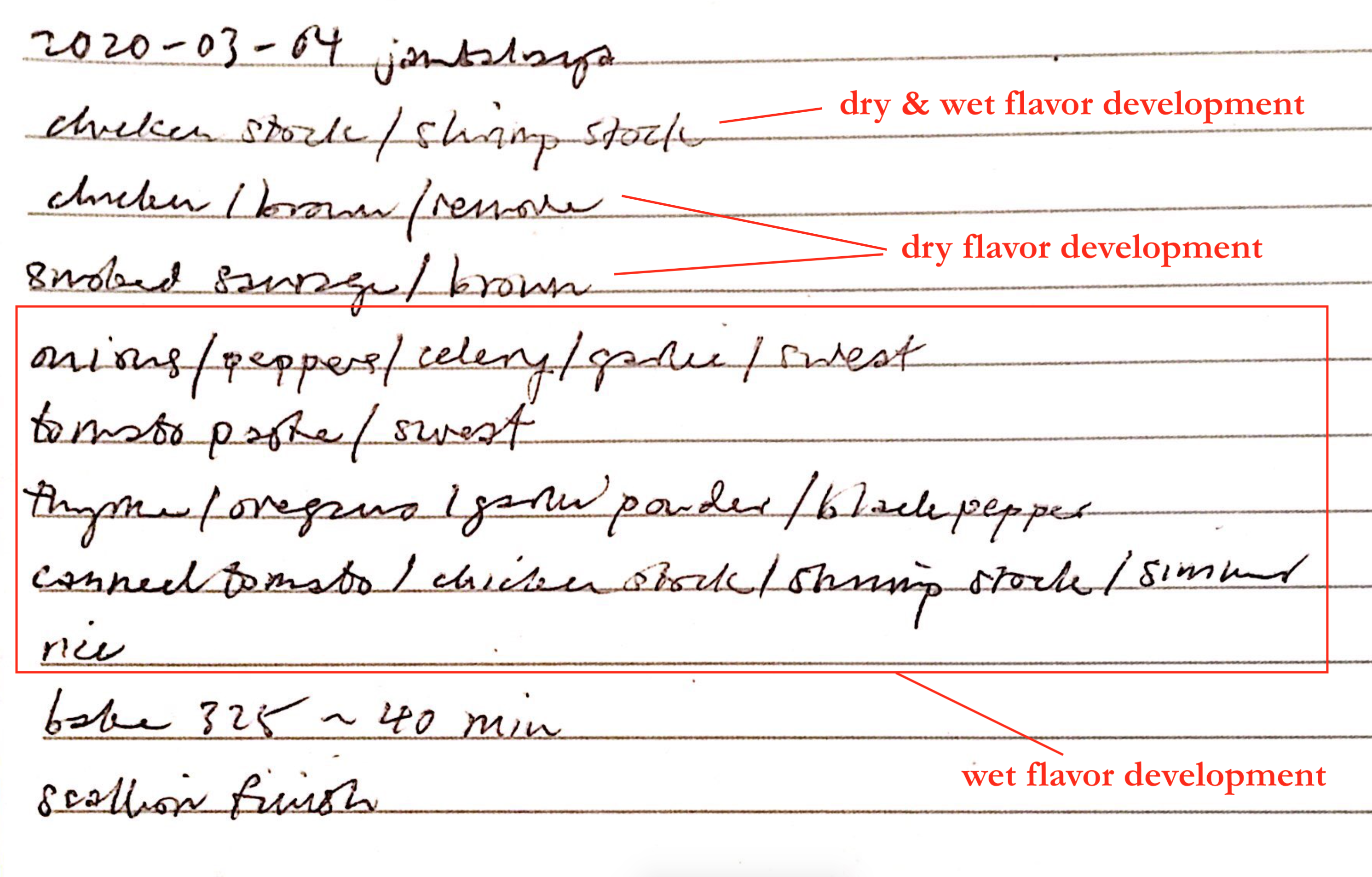

flavor development

Flavor development is arguably the most important part of understanding the concepts of cooking. As you already know, you must always season at every step, and taste, taste taste. Too many assumptions are made when you salt but don't taste, or don't taste at all. If you don't adjust now, you can't adjust later.

The next concept is probably a scientific concept you've heard of before. Maillard reactions. This is what's going on when you "sear". Browning is generally what it's called, and it's the reaction of proteins and sugars to create hundreds of flavor compounds. That's why steaks taste so good. That's why crispy dumplings taste so good. This is how you create deep, complex flavor with simple ingredients.

While it's not a hard and fast rule, the concept here is dry flavor development before wet flavor development. The Maillard reaction doesn't happen when there is water interfering with the reaction because it needs to get to a temperature beyond the boiling point of water (100°C at sea level). Let's look at how this is done.

- To get a dark, complex chicken broth, you roast the chicken carcass before creating the broth, compared to a light chicken broth with no bone roasting.

- The additional flavors of celery, onion, and carrot within the chicken broth come from wet flavor development, which is a simple diffusion of flavors into water.

- You sear the meat first to create pan fond (brown bits at the bottom of the pan). Some recipes (not this one) will utilize a wine to "deglaze" the pan, which really means "clean up the pot" and take all the fond into a delicious liquid. This is also why you don't "crowd" the pan, otherwise all the extruded liquid will end up stopping the Maillard reactions.

- You then add wet ingredients and sweat off the vegetables. As water leaves the vegetables, they also undergo some dry flavor development.

- Tomato paste is added and heated until it's roasty-toasty. All the while, sweating these ingredients allows water to evaporate away, which means, flavor concentration and some dry flavor development.

- Finally, the already flavorful broth is added and you've got yourself a tasty pot of liquid.

- Then, rice is added, and it's going to update the layers of flavor at every stage, along with seasoning.

- Add the meat back in.

With dry flavor development, there's always a battle with water. Every ingredient contains water. That's the sizzle of every ingredient that you put in. The key is keeping the water content low enough for the reaction to take place.

These flavor development steps is the key to why this jambalaya is going to taste a whole hell of a lot of better than something you just combine into one pot all at once. Let's recap the levels of flavor layering:

- complex flavors from roasty-toasty chicken bones (dry)

- flavors from other broth additions & aromatics (wet)

- complex flavors from meat pan fond (dry)

- flavors from sweating off vegetables (wet & a little dry as it sweats)

- flavors from herbs (wet & a little dry as it sweats)

- combining all ingredients to meld together (wet)

- insert into rice

- add back seared meats (dry)

- stir and combine (wet)

This way of organizing my cooking is what gets me excited about it. It reduces cooking down to repeatable concepts that are reusable in other recipes. You can see I don't worry too much about the amounts. This is partly because I am tasting to ensure I like what I'm eating at every stage. If that means more tomato paste, I'll add it. Don't let the recipe amounts deter you and your own taste buds.

Back to map of content (cooking)