lessons under the knife (michelin part 5, unusable parts, usable parts)

This is a re-sharing of a culinary experience that I had back in 2022, working at a 2* Michelin restaurant, Birdsong SF. I posted an eight-part series on Twitter at the time, but it was never formalized in a longer format. I'm doing this to sort of immortalize the experience here since it was some of my earliest beginnings of living according to my values, doing what I found interesting, and finding beauty.

It's an experience that helped shape my first sabbatical and I'm revisiting some of these learnings as they mix with conversations and readings in my current sabbatical.

Each part will be about the same with some grammatical and intonation fixes, plus an updated reflection at the end.

This is part five. Enjoy 😌.

unusable parts

"Frank, I don't understand why you put these uneven pieces in here."

My sous was picking bitter melon slices out and inspecting them one by one. He sighed impatiently, discarding one out of every three he was looking at.

I stood there, looking like an idiot. I didn't have a good explanation. I stammered an apology, and said I was cutting them rind side down.

"Yeah, but why did you put them in if you knew they weren't good? Also, that's not the way I showed you right? I was cutting them rind side up."

"Look, almost half of these are unusable. If I didn't catch them here, Chef would have my ass."

It's the feeling of "getting in trouble" that makes you never fuck up again because it's tied to an emotion (namely, embarrassment). It immediately taught me that anything I do is a reflection of the chef I'm working under, and as an extension, the head chef.

Anything that makes its way to a chef should be perfect as a standard, because each one of those melon slices will have eyes on it. My sous sees it, the Chef sees it, our guests see it. 👁 Most importantly, I see it too.

There's honor in having pride for your work. How you show up for the most menial and simplest of tasks is how you show up for something that really matters - executing a coveted recipe, making complicated broths and sauces, or handling the management of an entire kitchen.

I quickly realized that not all labor is equal. There's quality labor and shitty labor. Shitty labor loses money and trust pretty fast. Better to consistently do high quality labor slowly and ramp up the speed than the other way around. You save face and money this way.

usable parts

"Frank, try to have less trim."

My sous pointed at the hearts on my board and thumbed some of them.

"You can definitely use these and get some more out of this. Also, you gotta move faster."

He smiled.

Somewhere in the back of my mind I imagined shallots made from dollar bills - the olive green color, the rough texture of Benjamins, and the musty smell of old cash. I certainly didn't want to throw away money, right? 🤣

Maximal extraction really matters from a cost perspective. When I was asked to cut small, flat shallot squares, I was expected to use as much of the the shallot as possible.

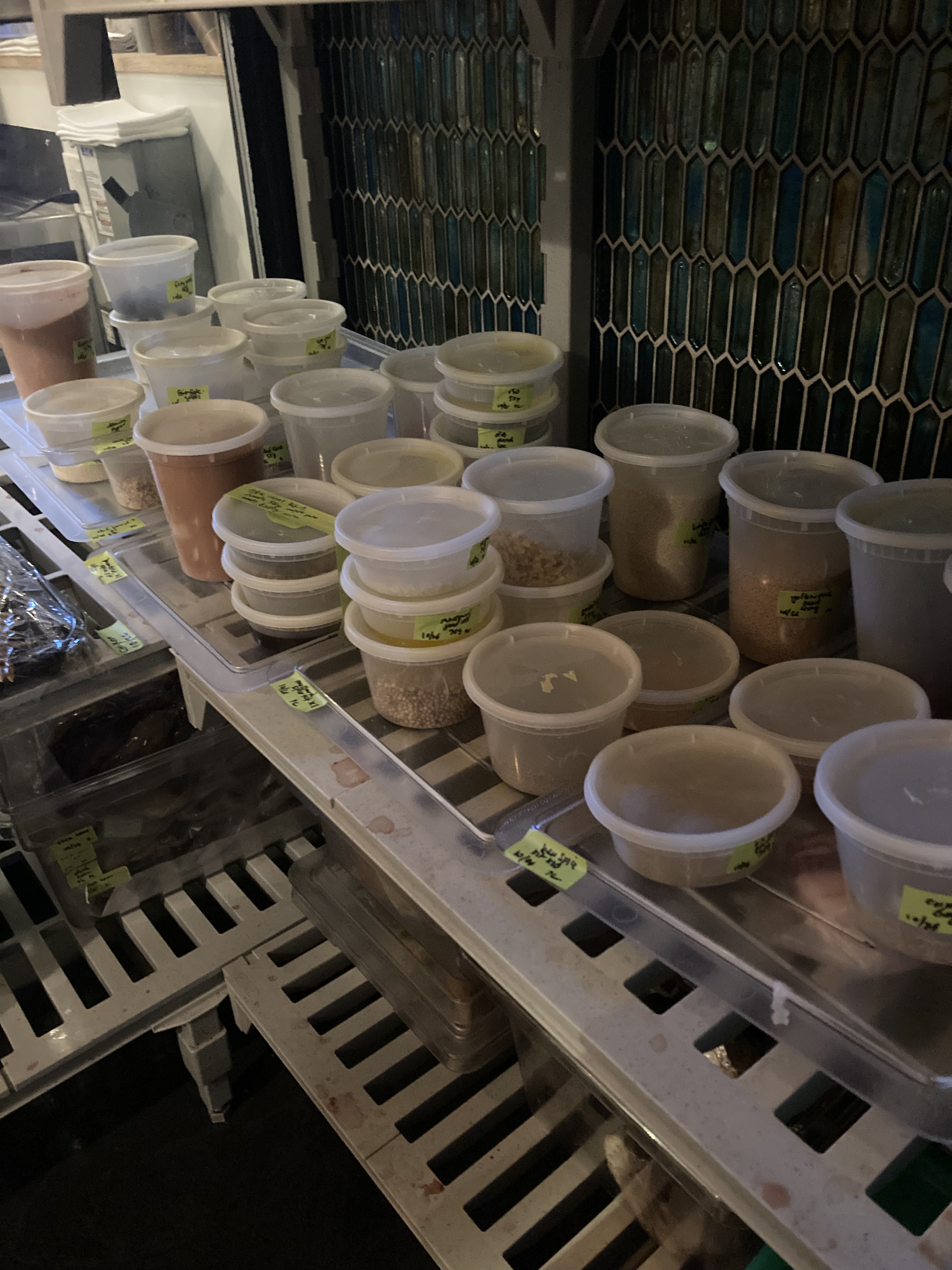

tubs of maximal extraction

tubs of maximal extraction

Produce is product, and product is money. There are times when we process ingredients and the trim is thrown away. If you suck with your knife skills, you'll be throwing away usable parts with the trim, and that's more money down the drain.

Before I started, I signed a contract with several informational clauses. Most of them dealt with standard intellectual property and legal cover for the restaurant, but one clause stood out to me:

"The restaurant will incur significant expenses as a result of having you here. The cost of materials that you will work on and therefore potentially lose is significant. Please be respectful of them."

This clause was the most important to me. Coming in, my goal was to be helpful. With no industry experience, I knew there were times where I was going to screw up or not move fast enough.

Working at Birdsong brought a lot of context to that particular clause and to the cost side of running a restaurant.

While there's an art, science, and honor to cooking, there's also the business side. In the context of expenses, restaurants are still businesses with small margins. Employees are expensive. Benefits are expensive. Great ingredients are expensive. Food is finicky, seasonal, and expires. When you're prepping, there's an infinite number of variables that could make things go wrong. Add in variables like equipment failure or plain ol' bad luck and that margin starts looking razor thin.

I've seen my sous rummage through a seafood delivery, poking, smelling, and looking at trout. Clear eyes, clean guts, firm flesh, good smell. Anything less than and it goes back with the purveyor. No purveyors gets to just drop shit off and leave. Imagine if we got fucked up fish and was out a couple of grand with nothing to serve. Not good. Standard of quality checks every day prevent this.

If the chefs are wasting product because they're messing it up, it eats into profit margins. That's why my sous was always on my ass about producing the least amount of trim and waste. That's also the reason why he was showing me a particular way of doing something. The faster I got it right, the more money I saved. It's a tough reality that lives alongside the art.

reflection

While this was an acutely painful experience that I recapped, I really liked the idea that your work not only speaks volumes to your own standards and work ethic, but your team around you and your predecessors.

As I sit here, I still see Instagram posts of excited diners at Birdsong SF. The dishes, as usual, look perfect. For me, I no longer just see the food. There's this feeling of quality, that a chef in the back learned the same things I did, and is holding the standard at a certain level. Identifying and chasing this philosophy of quality is perhaps one of the best things I've learned in the past few years. If you let it permeate everything that you do, and practice it alongside the muscle of beauty and wonder, you'll discover new levels to anything you do.